How low can you go?

For some people, the death of one parent and the incremental loss to dementia of the other would be bad enough. Or perhaps the risk of losing their job, even a dead-end, mindless job, with witless colleagues and an objectionable boss. But for Peter, these concerns are underscored by grief for his fiancée, Emma, and the guilt he feels for his part in her suicide. Having put everything on hold for three years trying to deal with Emma's death, Peter has become a passenger in his own life, spiralling into an increasingly destructive cycle of behaviour that can only have one outcome.

Or can it?

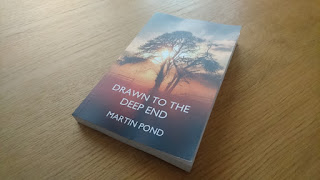

Drawn To The Deep End is an honest and, at times, darkly comic portrayal of what it is to be a young man alone and adrift in 21st Century Britain. It is Martin Pond's first novel, available exclusively from Amazon.

"This is a painfully truthful story of a man slipping ever deeper into the mire.

A sharp and powerful piece of writing, with a darkly comic sense of humour under the surface."

Ian Nettleton, author of The Last Migration and Out Of Nowhere.

"Couldn't put it down. Grimly gripping!"

Bridport, Canongate and Escalator award-winning author Lynsey White.

Excerpt

Driving home tonight, I decide to turn off from the main road, and do the last seven or so miles of my journey cross-country. I tell myself this is on a whim. Whatever the reason, it makes a nice change - the narrow green lanes are preferable to the straight grey of the A road, even if it does take twice as long to cover the same distance.

After I have had to back up to let a tractor pass and squeeze the Polo into the neck of a farm track to let a Range Rover through (far be it for the off-roader to go off road, of course), I remember why I don't come this way more often. One of the reasons anyway. Still, it's shaping up to be a beautiful summer's evening - sunlight is finding its way through the creaking branches of trees to my left. Nature's heliograph. Thoughts of Alan, Craig, BuyLo customer profiles and Steer House start to dissolve.

I turn left into Long Lane - well, that's what we called it when we were kids. It's an unnamed road on maps, if it's even shown at all. Lined on both sides with trees that meet overhead, the lane is a dark tunnel after the dappled, slanting sunlight. I put the Polo in neutral, take my foot off the accelerator and let myself gather momentum down the steep decline.

We roll, the Polo and I, daring each other not to touch the brakes. Long Lane is narrow, and by the time we're half way down it feels reckless to take the kinks and bends at such speed. Just before the bottom though, just before we pop like a champagne cork back into the sunlight, cornfields on either side, I know that I must start to slow down, that there is that sharp corner coming. I ease onto the brakes and drop the Polo back into gear - it complies with the mildest of grinding complaints.

Just after the corner, there is a tiny lay-by on the left, and I pull over and switch off the car. I don't know if I want to do this. I haven't done it in a while, but it seems right somehow, especially given what I'm going to do tomorrow. After all, I didn't really come home this way on a whim, did I?

I walk back to the corner and step up onto the verge so that I can lean on the fence that separates the field from the road. Here, in the shade of The Tree, it feels surprisingly cool but then, given the size of the oak, this particular spot probably hasn't been in the sun since mid-morning. There is no way you could tell, from looking at The Tree, that it had been in a fight with Emma's car. It was more than three years ago, I suppose. And like I said, when it's car versus tree the tree nearly always wins. Even so, I always expect to see something when I stand here - I always hope that The Tree bears a scar. The casual observer wouldn't even notice the difference in the fence. I can only see it because I know it's there: the way the creosote is slightly less weathered on this beam than on all the others.

I stand here, looking at The Tree and losing track of time. There is no traffic - no-one comes this way if they can help it. It's so quiet, I can hear individual voices in the insect life of the field beyond, each buzz, every chirrup. The sun is so low now it's making its way back under the canopy of The Tree. It is idyllic, and so I try to replay good times: that week in the Italian Lakes, moving Em into her new flat, the weekend in Brighton when we joked about who would push whom along the prom when we were old and grey.

The trouble with reliving moments though is that they tend to give rise to what happened next, and soon I am reliving other times. Before long, I am replaying the last argument we had, the one in which she asked if I knew what uxorious meant. I accused her of throwing her education in my face and stormed out without saying goodbye. The next time I saw her was at the hospital, and by that time she couldn't hear me, whatever I said to her.

I step out from under The Tree, and resolve to stop coming here. It's well after seven, and time I was getting on.